The War Years (1941 – 1946): Serving the U.S.

100th Infantry Battalion

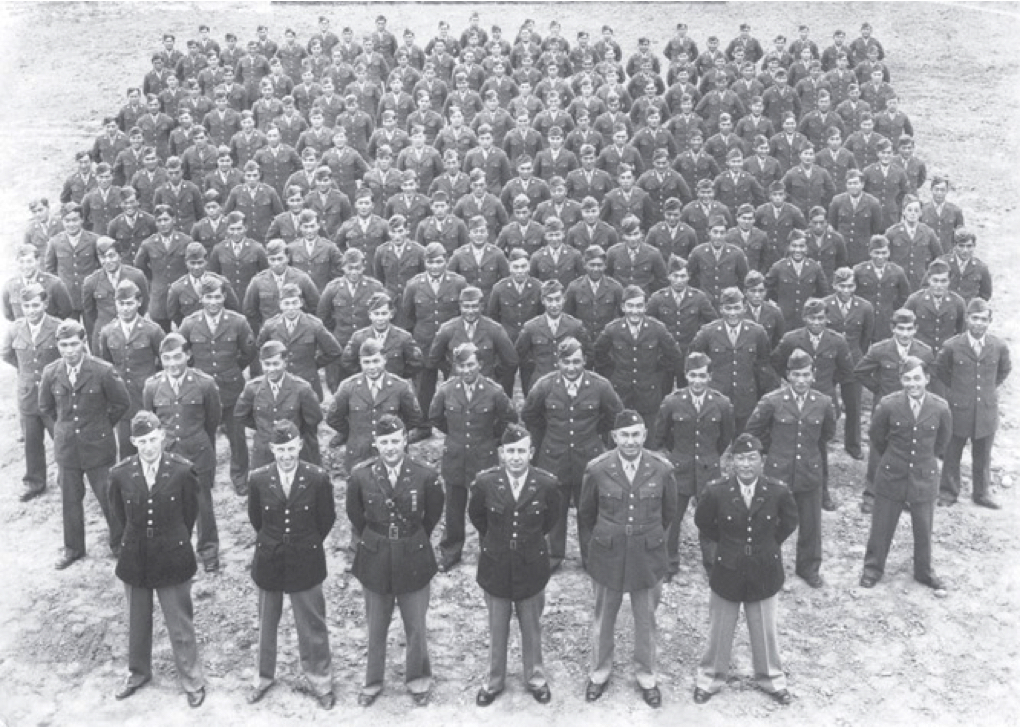

With the exception of a few of its officers, the 100th Infantry Battalion was the first combat unit in U.S. Army history to be comprised exclusively of second generation (Nisei) Japanese Americans.

When Japan mounted its surprise attack on Pearl Harbor on Sunday morning, December 7, 1941, many Japanese-American men were serving in the 298 and 299 Infantry Regiments of the Hawaii National Guard. As the initial shock wore off, the loyalty of Americans of Japanese Ancestry, or AJAs, came into question and was debated for months between Honolulu and Washington.

Many political and military leaders in Hawaii defended the AJAs and urged that they be given the chance to prove their allegiance to America. Finally in May, 1942, the Army made a decision.

AJA soldiers of the Hawaii National Guard, the Army Reserve and regular Army were formed into a provisional battalion. It was to be “reorganized, equipped, and trained for future use as an infantry combat unit to be ready for field service on 10 days’ notice after September 30, 1942.”

This resulted in an oversized battalion of 1432 soldiers. It was designated the 100th Infantry Battalion (Separate), meaning it did not yet belong to a regiment or other larger unit.

On June 5, 1942, they shipped out of the Islands in the darkness of night; their destination a secret. Several days later, San Francisco’s Golden Gate Bridge appeared on the horizon. After disembarking in Oakland, the soldiers were transported by train to Camp McCoy, Wisconsin, then to Camp Shelby, Mississippi, for 16 months of combat training.

In September 1943, the 100th was dispatched to Oran, Africa. On September 22, 1943, the “One Puka Puka” (Hawaiian Pidgin English for “one zero zero”) hit the beaches of Salerno, Italy as part of the U.S. Army 34th Division.

During a forty-day struggle, the Original 100th was left with only 521 men. It was after this campaign the 100th became known as the “Purple Heart Battalion.”

For the next nine months, the 100th fought from Salerno to Rome, battling a tenacious enemy throughout a bitter winter. The unit faced its toughest test at Monte Cassino, a mountaintop monastery occupied by the Germans. Against insurmountable odds, during a forty-day struggle, the Original 100th was left with only 521 men. It was after this campaign that the 100th became known as the “Purple Heart Battalion.”

On June 11, 1944, replacements from the 442nd Regimental Combat Team (a Nisei fighting unit made up of volunteers from Hawaii and the mainland United States who went into training just before the 100th left Camp Shelby, Mississippi) bolstered the casualty-depleted 100th. Initially an independent battalion, the 100th was subsequently designated the first Battalion of the 442nd, although it was allowed to retain its original name.

By September 1944, as part of the 442nd RCT, the 100th contributed significantly to driving the German army north to the Arno River. From October through November 1944, the 442nd joined the 36th Infantry Division in northeastern France for the Vosges Mountains campaign.

The 442nd was then attached to the Fifth Army in Italy, and in April 1945, it pierced the long-held Gothic line and drove the German enemy back into the Po Valley, forcing Germany’s surrender on May 2, 1945.

As a battalion of the 442nd, the 100th participated in the liberation of Bruyeres and Biffontaine and the rescue of the Texas ”lost battalion” – an effort that earned it a Presidential Unit Citation.

During its 18 months in combat, the 100th Battalion buried 342 of its men. For its service to America, the 100th was honored with 3 Presidential Unit Citations, 30 Division Commendations, 1703 Purple Hearts, 8 Congressional Medals of Honor, 17 Distinguished Service Crosses, 147 Silver Stars, 238 Bronze Stars for Valor, 8 Soldiers Medals, 9 Legions of Merit, and 2,173 Bronze Stars for meritorious service.

Said Lyn Crost, a war correspondent and author of Honor by Fire, “As years pass, statistics of casualties and decorations may be forgotten, but the record of the Original 100th Infantry Battalion, and what it meant to the acceptance of Japanese Americans as loyal citizens, must be remembered. By fighting for values and concepts of the United States, the Nisei set an example for people of all nations who seek sanctuary here.”

Edited From “Japanese Eyes, American Heart” 1998. Reprint Approved By Ted Tsukiyama, Esq.,

100th Infantry Battalion Education Center Brochure, Text By Richard Halloran.