The War Years (1941 – 1946): Incarceration

Incarceration of Persons of Japanese Ancestry

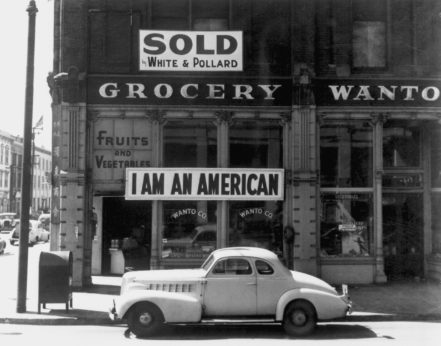

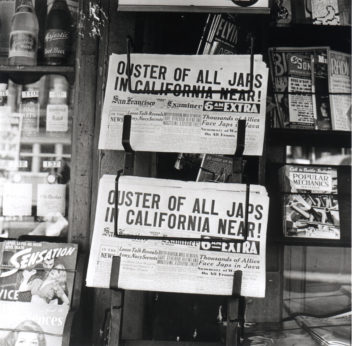

Following Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor, anti- Japanese sentiment reached a fevered pitch. Japanese who immigrated to America in search of economic opportunity as well as Americans of Japanese ancestry became victims of mass hysteria.

The U.S. government feared that these groups would betray America through sabotage or espionage. Despite the lack of any concrete evidence, Japanese Americans were suspected of remaining loyal to their ancestral land.

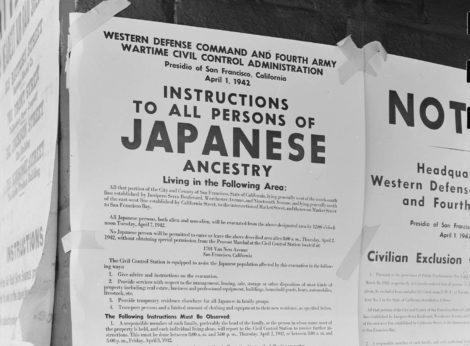

On February 19, 1942, President Franklin D. Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066, which established two military zones: the west coast of America and the Territory of Hawaii.

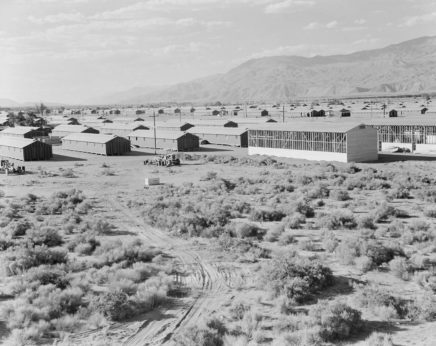

The military governor of the west coast zone incarcerated 120,000 ethnic Japanese; almost two thirds of them were U.S. citizens of Japanese descent. They were forcibly removed to 10 camps far from population centers. Second generation Japanese Americans (Nisei), already in the U.S. Army, were discharged or reassigned.

Hawaii faced a more imminent danger of invasion, but the military governor there decided against mass incarceration. Advisors told him that 1,500 suspects were already apprehended; Hawaii needed Japanese Americans to maintain its economy.

Personal Losses

Fearing that Japanese Americans represented a threat to national security, authorities on the west coast gave Japanese immigrants and Japanese Americans as little as 24 hours to leave their homes and businesses for hastily constructed camps. Each person could take only what he or she could carry. Many sustained huge financial losses. They were forced to sell their property quickly to predators who offered them pennies on the dollar. Many left behind irreplaceable personal property and family heirlooms.

What do you call the camps?

The Power of Words

During World War II, the government called them “relocation centers” and “assembly centers.” Others called them “internment camps.” Such euphemisms mislead the American people. They mask the fact that 120,000 innocent Americans were forcibly removed from their homes at gunpoint and imprisoned for years in deplorable conditions without due process of law – simply because of their race.

Many today argue that these euphemisms should be replaced with phrases that reveal the truth of what happened. Some historians go so far as to argue that the camps should be called “America’s Concentration Camps.”

The Merriam Webster Dictionary defines “concentration camp” as “a facility where persons (as prisoners of war, political prisoners, or refugees) are detained or confined.”

Lane Hirabayashi, Professor of Asian American Studies at UCLA, distinguished three major types of concentration camps in a “Power of Words” workshop during the National JACL Convention in 2012: Nazi death camps, Soviet labor camps, and Japanese American camps. They vary in severity but all are concentration camps.

Abbie Salyers Grubb also addressed this dilemma in her PhD dissertation. Although the camps holding Japanese Americans during WWII meet the technical definition of concentration camps, she argues that that term has become so inextricably linked with Nazi death camps that it misrepresents conditions in American camps.

The NVN’s interest is in historical accuracy, not advocating a point of view on what to call the camps. Therefore, throughout this web site, we will simply refer to the camps as camps, describe conditions inside them, and let readers supply their own adjectives.

Words have the power to reveal truth and obscure it. To preserve democracy and prevent future abuses of freedom, it is important for future generations to understand what truly happened.

Conditions in Camps

In desert camps, the evacuees met severe extremes of temperature. In winter it reached 35 degrees below zero, and summer brought temperatures as high as 115 degrees. Rattlesnakes and desert wildlife added danger to discomfort.3

The “evacuees” first went to 17 temporary assembly centers, such as the Santa Anita and Tanforan race tracks, to await transfer to camps.

In some cases, family members were separated and put in different camps. Barbed wire ringed each camp. Army personnel manned sentry towers with machine guns around the clock. Detainees knew that if they tried to flee, sentries would shoot them.

The hastily built camps contained tar-paper-covered barracks with no plumbing or cooking facilities. One light bulb hung from each ceiling. Many camps contained only outhouses; toilets contained no partitions.

Some internees died from inadequate medical care or the high level of emotional stress. Each person had one army cot and received just 45 cents worth of starchy food per day.

A doctor at Tanforan described the diet of people in these camps, “There is no milk for anyone over 5 years of age… No meat at all until the 12th day when very small portions were served… Anyone doing heavy or outdoor work states they are not getting nearly enough to eat and they are hungry all the time. This includes the doctors.”2

The Army located these camps ‘at a safe distance’ from any locations perceived to be strategic. The environments of the camps ranged from swamplands in Arkansas to deserts in Arizona. The land was generally barren, isolated, and harsh.

1 “What’s In A Word?” Introduction To “the Internment Of Memory: Forgetting And Remembering The Japanese American Experience During World War II.” Copyright 2009 Abbie Salyers Grubb.

2 Living Conditions Of Japanese American Internment Camps

3 Personal Justice Denied: Report Of The Commission On Wartime Relocation And Internment Of Civilians.