We continue to celebrate Women’s History Month by sharing the story of Tec 4 Takako Kusunoki, a veteran of the Women’s Army Corps (WAC) during World War II.

Born in 1921, Takako Kusunoki was the daughter of Japanese immigrants, Kotaro and Chitose Kusunoki. She and her two older sisters, Yachiyo and Kinuye grew up in the small town of Colusa, CA, located right along the Sacramento River. All three sisters were artistic and highly creative, each following their interests in fashion design, art, illustration, and journalism. When Takako was 14 years old, her father died as a result of a tragic accident at his restaurant. Her mother, Chitose, who had worked alongside him, took over and continued to work in the restaurant business as a manager and owner.

As a student at Colusa Union High School, Takako was active in many clubs, including the Scholarship Society, Spanish Club, and Yearbook Staff. During her senior year, she served as the editor of the school’s newspaper, The Arrow.

As a high school graduate, Takako discovered that employment was limited for Japanese Americans, especially after the onset of WWII. She and her sister Kinuye found jobs as domestic workers, yet Takako managed to find a part-time position at the local newspaper, the Colusa Sun-Herald, allowing her to continue her interest in journalism.

On December 7, 1941, the Kusunoki’s lives took a dramatic turn when Japan attacked the U.S. naval base at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, catapulting America into World War II. Two months after the attack, the Attorney General of CA, Earl Warren, requested a map of Colusa as part of its “Alien Land Law Survey”. Colusa’s district attorney responded and quickly sent him profiles of every Japanese American that lived in the tight knit community, along with maps indicating where they lived.

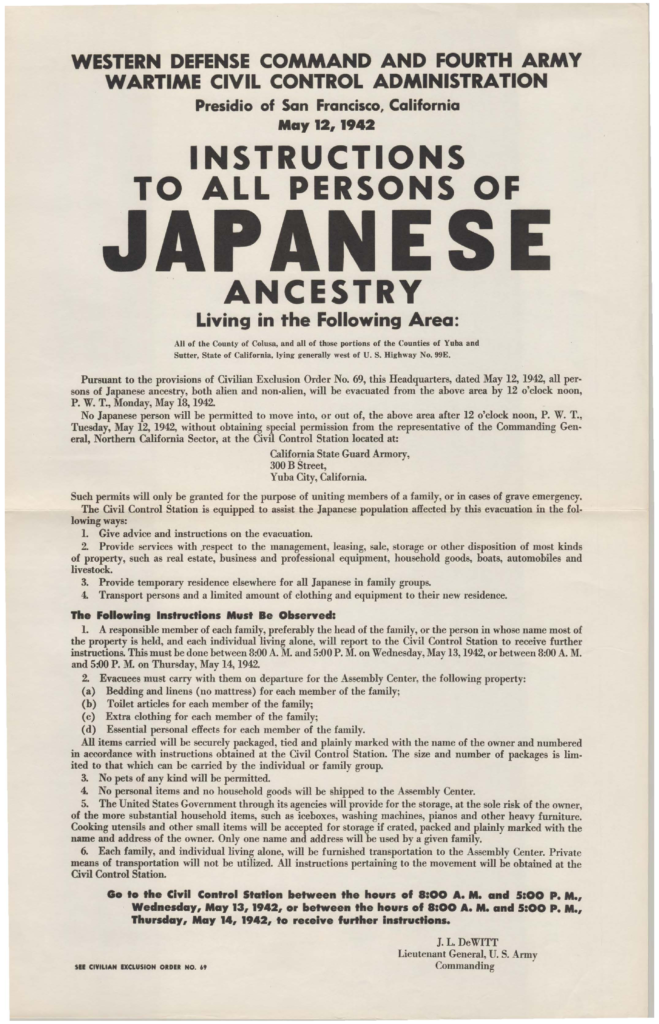

On February 19, 1942, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, approving the War Department’s removal of Japanese Americans living on the West Coast. Exclusion Orders followed and were posted on telephone poles and on sides of buildings, directly targeting “all persons of Japanese ancestry, both alien and non-alien.” In the span of a week, the Kusunoki family would be forced to give up their business, home, a majority of their possessions, and their family dog, an experience that was particularly hard on Takako.

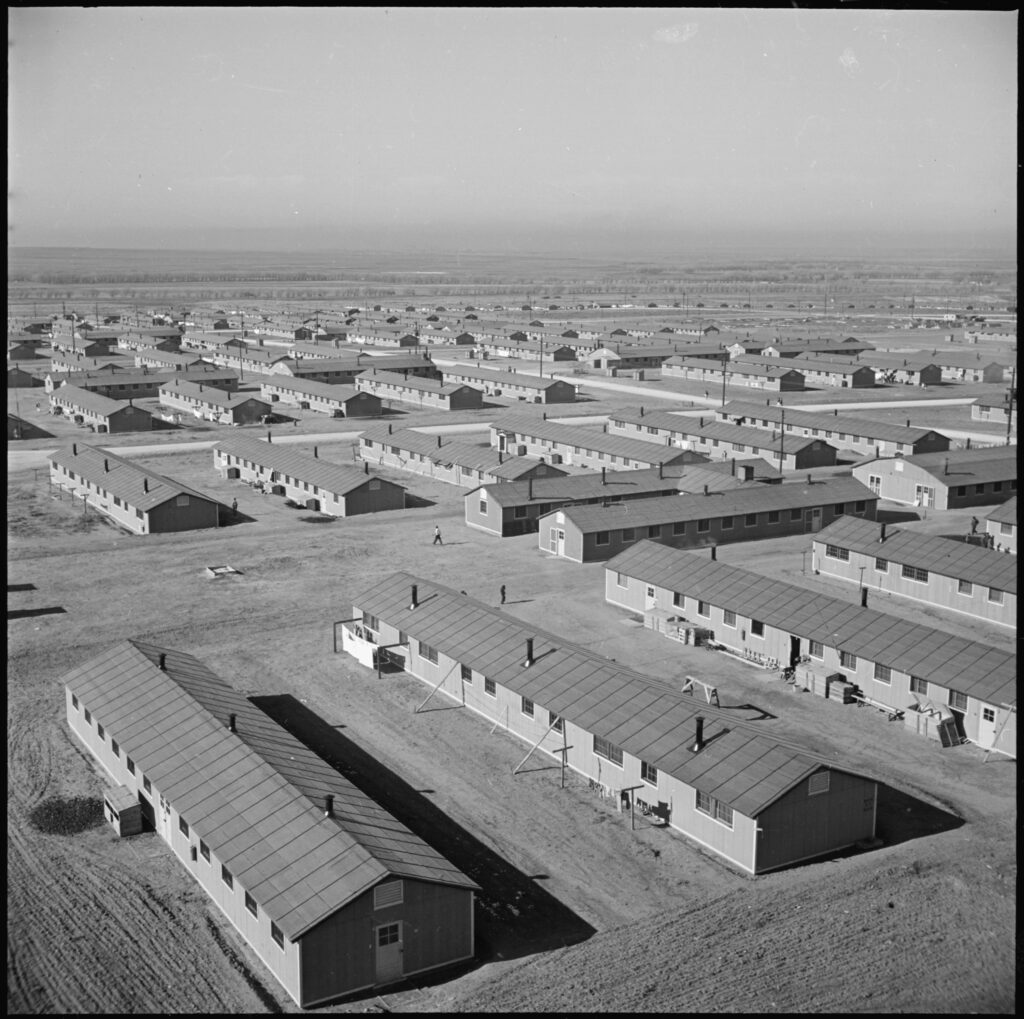

After spending several months living in a temporary assembly center at the Merced County Fairgrounds in CA, the Kusunoki family was sent to Colorado and transferred to the Granada Concentration Camp – more commonly known as Amache – in September 1942. At its peak, Amache held approximately 7,300 individuals of Japanese ancestry, two-thirds of whom were U.S. citizens.

The size of a small town, Amache developed its own ecosystem, with its inhabitants filling needed positions in construction projects, as doctors and nurses, in farming…and with the camp’s newspaper, The Granada Pioneer. By the time the second issue rolled out – Takako was part of the newspaper’s staff of writers.

Less than a month later, she was writing her own column called “Between Us Girls” as ‘Taxie’ Kusunoki, a nickname given to her years ago because her name had been too difficult for others to pronounce.

The column highlighted Takako’s ability to walk the tightrope of addressing women’s issues and the goings on at Tule Lake with her finely-tuned sense of humor. She worked there for one year, experiencing a stint as Acting Editor during her time with the paper.

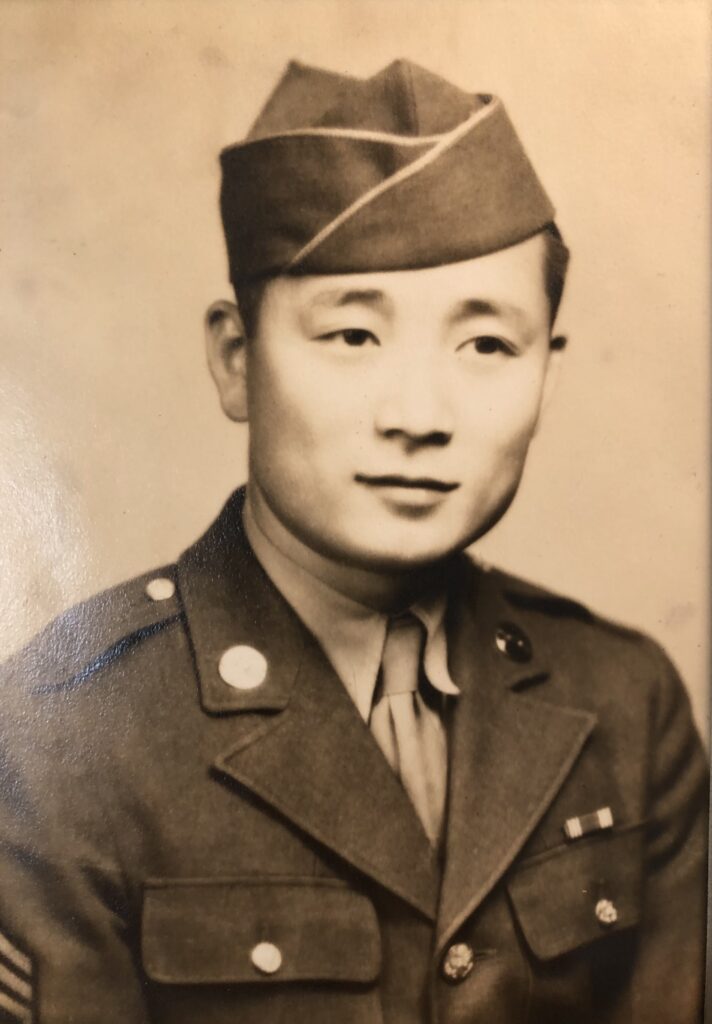

In October 1943, Takako obtained an early release from Amache. She headed to Kansas City, MO and eventually moved to Cincinnati, OH. While walking in town, she happened to notice a recruitment sign for the Women’s Army Corps (WAC). Intrigued, she entered the post office where she met and spoke with a recruitment officer. Soon after, she signed up to join the U.S. Army and headed to Fort Des Moines, IA to go through basic training at the WAC Training Center.

After completing basic training, Takako served at MacDill Field (now MacDill Air Force Base) in Florida and at the Pentagon in Virginia, where she primarily worked as a typist, handling highly restricted information. Takako recalled, “I was already assigned to, well, you can guess. To type. What I typed – and there was a whole bunch of us – was secret documents. Secret documents! You would have thought they wouldn’t let me! I just found it very funny.” She spent over one and a half years serving in the WAC and received the Victory Medal, American Theater Ribbon, and Good Conduct Medal.

Takako was discharged from the WAC in 1946 and she immediately went to visit friends back in her hometown of Colusa and in San Francisco. She made her way to New York to visit her older sister, Yachiyo, and eventually settled there, finding herself back on a path that she had left back at the Amache Concentration Camp: Journalism. Kakutaro Inoue, editor of the Japanese language newspaper, the Hokubei Shimpo, had been searching for an English language editor and upon meeting Takako, immediately offered her the job. She accepted.

Through her work at the Hokubei Shimpo, Takako covered politically active, progressive groups such as the Japanese American Committee for Democracy and the Nisei Progressives. She met jazz luminary Louis Armstrong, striking up a friendship and maintaining an ongoing correspondence with him. Most of the Japanese Americans living in New York City mixed in the same social circles, and it was through these circles that she met Steve Shigeo Wada.

Steve Wada was originally from Loomis, CA, and grew up in Hiroshima, Japan. His Japanese language skills and cultural knowledge of Japan made him an ideal candidate for the U.S. Army’s Military Intelligence Service (MIS). During WWII, he served as a Japanese language instructor at the MIS Language School at Fort Snelling, MN

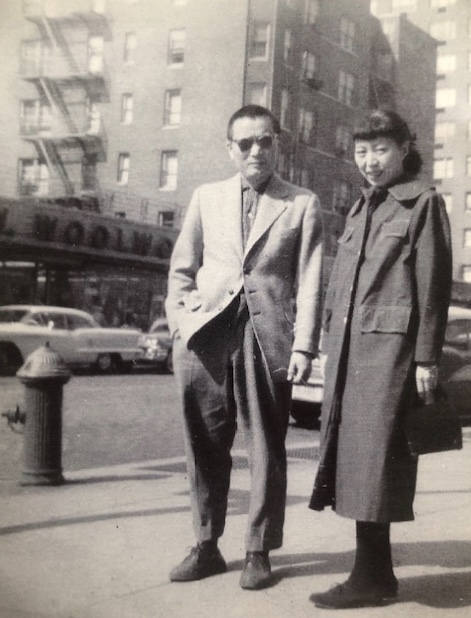

A serious artist, Steve had studied at the Art Institute of Chicago and the Art Students League of New York. Upon meeting Takako, they both travelled to Paris on the G.I. Bill to study painting at the studio of Fernand Léger. When they returned to New York, they married.

Reading the New York Times, 1959

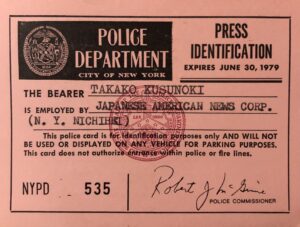

Takako continued her work in the world of journalism by returning to her previous position at the Hokubei Shimpo, which had been renamed the New York Nichibei, and became involved in the Asian American civil rights movement. She worked at the Nichibei until her retirement in 1983.

“Mom was a shy person…always ducking into the back row of group pictures.” Daughter Stephanie shared during Takako’s memorial service. “Mom was also very modest about her past and her accomplishments.” Her sister Jennifer shared, “She was a really good writer. She had a wonderful style that I still marvel at…it reflected her love of good writing and her aptitude for it; it was a reflection of the care and grace with which she felt it was important to treat her friends, and most anyone she met.”

Takako Kusunoki passed away in 2016, leaving a legacy of strength, an intuitive thoughtfulness, and a deep integrity that is carried on by her two daughters.

Photos courtesy of Stephanie and Jennifer Wada, Library of Congress and the National Archives